On September 12, turning south off Hwy. 11, I travelled several klicks until I reached the first stop sign. Looking right, I found the Marathon museum. After I had called Jim Collins, he met me there.

Jim, President of the Marathon & District Historical Society and Museum, is instantly recognizable by his Wyatt Earp moustache. Retired from the now decommissioned pulp and paper mill, he has a wealth of knowledge behind the moustache.

Jim let me in the back door; the museum is closed for the season. Mindful that I could spend only a limited time, he gave me a quick tour. It is not the museum I remembered. I remembered a rather chaotic jumble of artifacts and photos and maps, kind of like the jumble I enjoy browsing in used book stores. For the 75th Anniversary of the the community in 2019, the building had received a major upgrade.

The jumble is gone. One wanders down uncluttered aisles under bright ceilings and between white walls. On display are posters and panels and photographs ̶ loads of photographs ̶ some on long white tables, along with artifacts.

Jim drew my attention to the Boy Scout uniform of a former member of the Society ̶ the late Dick Fry ̶ who was once a summer camp neighbour of mine. Jim grew up in Boy Scouts, and took care to mention the Boy Scout Forest I had driven through to get to the museum. He alluded to Skin Island, a notorious encampment during the building of the CPR. You’ll have to look it up yourself.

Beside the Scout uniform there was a naval captain’s uniform, I didn’t catch the name. But we both skimmed over a centre piece display featuring the Peninsula. It’s a long story.

There is a model of the tug boat that rafted wood from the Pic River and brought it to the mill at Marathon. Jim said the Peninsula began life as a World War II vessel and that there is only one other like it now in Canada. I have since researched this boat and can summarize its history.

In 1943, the Royal Canadian Navy commissioned the HMCS Norton. In 1946 the boat was converted to private use and renamed the Peninsula. In 1946, Marathon Paper Mills of Canada acquired her, and for twenty-odd years she collected the logs driven down the Big Pic River. For the next phase of her life, she operated out of Thunder Bay, and then sat quietly rusting in the harbour. The Marathon Historical Society planned to raise $100,000 to purchase her, and in 2018 arranged to drive her to Peninsula Harbour.

Thence began a sad saga. The Peninsula was beached. She was intended as a static display. Problem after problem arose. A study commissioned by the Town determined that the boat was a time bomb of hazardous material.

The hazards encompassed asbestos, benzene, lead, mercury, PCBs, and 67,000 litres of diesel, oil, and contaminated water. The price tag for demolition totalled $258,500, not including legal fees and administrative time.

Meanwhile, visitors delighted in the old Peninsula, and on occasion clambered all over her and poked into her dark corners. In late 2020, the old girl was dismantled and buried.

I signed the guest book. Jim then led me into back rooms of the museum, which are located a few blocks away in the Lakeview Community Centre. These are where the hidden treasures are located in any museum, and very few of the public get to see them.

I had asked to see an historic map of the Big Pic Forest Concession. I have an interest in the Industrial Road, Slingshot Creek, and old Camp 12, just west of Manitouwadge, because my next novel will feature them. Jim peeked into a second-floor room which seemed chock full of files and photos, and then led me outside to a ground-floor annex which was chock full of artifacts and, yes, a pile of maps.

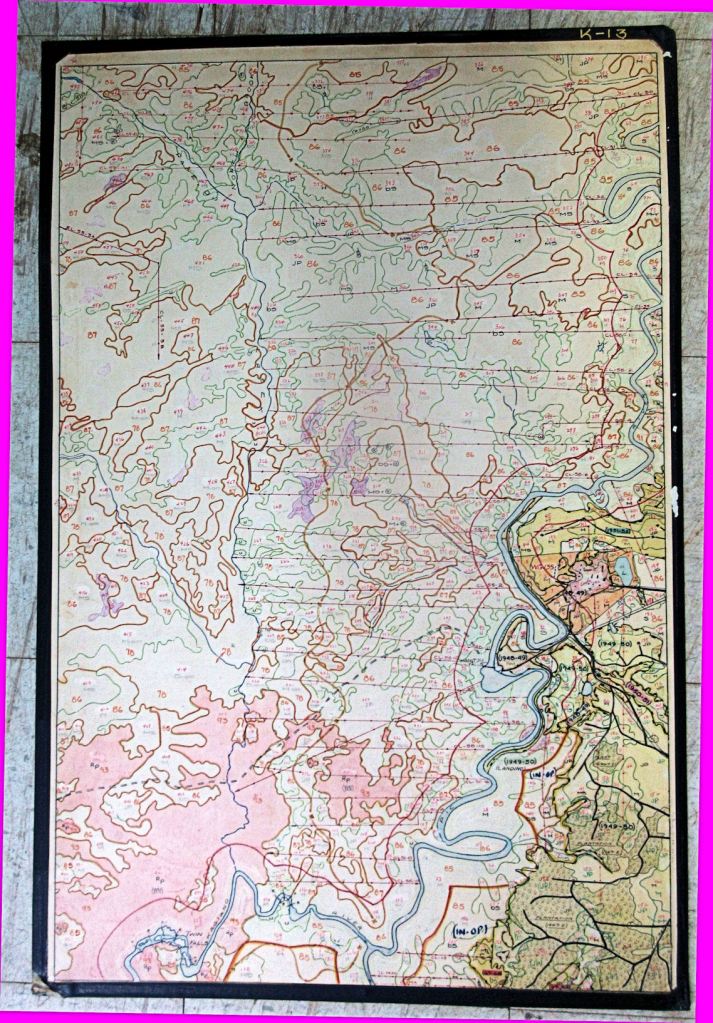

Jim said the FRI maps were at donation when the mill closed. There must have been a hundred of them. Each was mounted on a stiff backing measuring approximately 18 by 30 inches. These Forest Resource Inventory maps were beautifully hand-drawn and hand-coloured. A collector would give his eye teeth for one. I was tempted to offer my front teeth for one.

We started sorting out the maps. I had my eye on my watch; I was supposed to be meeting my brother, John, for supper in Manitouwadge. Finally, success! The 49th or 50th one depicted most of my area of interest. The other 50 I would leave for another day.

Museums are fine places to find old books. Before I left, I spotted an ancient and tattered copy of Pic, Pulp and People: A History of the Marathon District, by Boultbee and Embree. I surmised that hundreds of visitors had thumbed through it. A copy is being offered on the Internet for USD $199.95. Fortunately, I have my own copy.

And, hopefully, I will eventually have my own fictional history for readers. The working title of my novel is The Manitou Firebird.

The best question is how and why this beautiful Canadian boat was scraped?

Very sad, considering the time and money used to bring this beautiful vessel to Marathon..

Who was the Person/Educated elite to cost such a grave outcome?

Hopefully not some tire guy with an undivided perception of what he volculized to an small minded construction company.

Very Sad for the town of Marathon

LikeLike