Yes, timber wolves are a protected species in Ontario except when and where they are not.

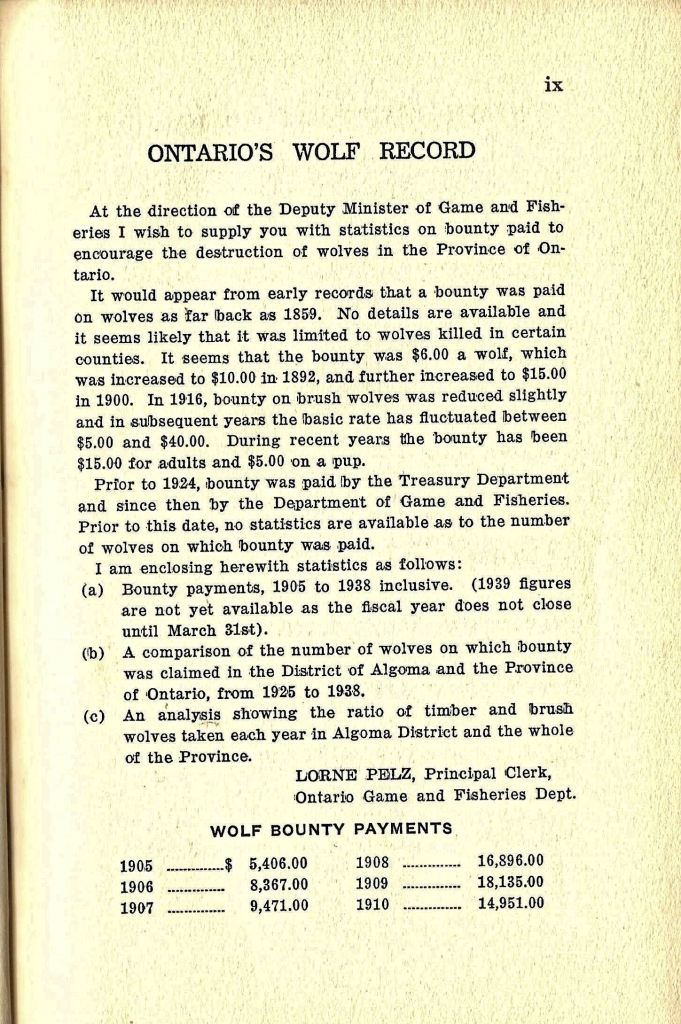

Almost from the beginning, Ontario tried to extirpate its wolves. Yes, “extirpate”, meaning something like “to encourage the destruction of wolves” (1914 Wolf Bounty Act). The first bounties began in 1793, when Ontario was still Upper Canada (“Of Bounty and Beastly Tales: Wolves and the Canadian Imagination”, Stephanie Rutherford, Trent University, 2019).

About midway through the twentieth century, lawmakers twigged to the fact that wolves were still flourishing. That placing a bounty on the head of every Canis lupis ̶ male, female, or pup ̶ might actually aid the species to survive.

When James W. Curran asked the Department of Games and Fisheries to supply him with stats on the destruction of wolves, he got this document, which became the first chapter of this book.

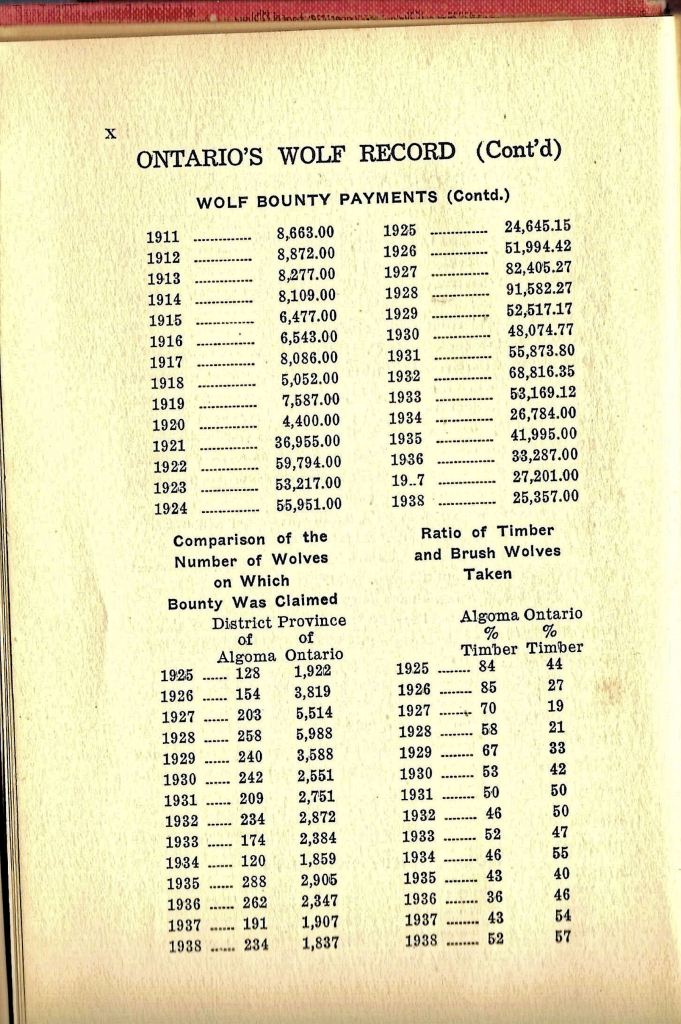

In 1905, hunters collected bounties amounting to $5,406.00 for proof of timber wolves (i.e., gray wolves) and brush wolves (coyotes) killed. In 1905, a wolf and coyote bounty was $15.00 (“The Bounty System in Ontario”, D.N. Omand, Wildlife Society, 1950). In 1920, the bounty on coyotes was raised to $20.00; on wolves, to $40.00. Bounties paid in 1920, $4,400.00. In 1921, $36,955. In the conclusion to his research, Omand writes “The evidence available indicates that this expenditure has had practically no effect on either the timber wolf or the brush wolf population of the Province”. Remember, Omand was writing in 1950, a century and a half after Ontario established the bounty system.

Note a typo in the section “Ratio of Timber and Brush Wolves Taken”. One subsection is “Algoma % Timber [Wolves]”; the next subsection should read “Ontario % Brush [Wolves]”.

The last nail was driven into the coffin by researcher Douglas Pimlott, a biologist with the Department of Lands and Forests (Rutherford 2019). In 1963 he published his findings, “that wolves preyed selectively on the old and weak, particularly in the winter (they kill what’s easy to catch); that wolf overkill was the exception rather than the rule; and wolves have a ceiling to their population, usually one wolf per ten square miles”. Breeding pairs would always be able to make up for losses from hunting .

Finally, as evidence mounted higher and higher, Ontario lifted the bounty of wolves in 1972. The Act was replaced with Wolf Damage to Livestock Compensation Act. Today, wolves of whatever label are treated as fur-bearing animals. Hunters must have an Outdoors Card, a Small Game Licence, and proof of firearm accreditation. In a handful of Wildlife Management Units (WMUs), there is open season on hunting year round. In another category of WMU, the season is open from September 15 to March 31, and hunters must have a wolf/coyote tag. In a third category, the season is closed year round in Provincial Parks, Crown Game Preserves, and contiguous counties.

The author James W. Curran was writing his book well before researcher Omand published his findings. At one point, Curran writes, “Has it been worth while to try to destroy the legend of the wolf’s ferocity. The writer thinks so. Probably nobody in Canada, at least, believes in it today. Perhaps mankind would treat all wild life more humanely if the facts were really known . . . “

C’mon, James! Nobody in Canada believes it today? Dream on, the myth is alive and well in Northern Ontario.